The Thing

Thomas Jefferson made sure that Richard Henry Lee saw two versions of the Declaration

On June 7, 1776, on instructions from the Virginia Convention and on behalf of the Virginia delegation in the Continental Congress, Richard Henry Lee offered three resolutions: one for independence, one for confederation, and one for treaties with foreign powers. Soon after, Lee travelled from Philadelphia back to Virginia, so he did not participate in drafting or debating the Declaration of Independence.

Thomas Jefferson made sure that Richard Henry Lee saw two versions of the Declaration: the committee draft, as Jefferson had intended the text, and the final version, as approved by the Congress on July 4. Or, as Jefferson described the two documents in a letter written to Lee on July 8: “I enclose you a copy of the declaration of independence as agreed to by the House, and also, as originally framed.” Jefferson predicted that Lee would “judge” whether the Declaration was “the better or worse for the Critics”—the other delegates in the Congress who had edited the text.

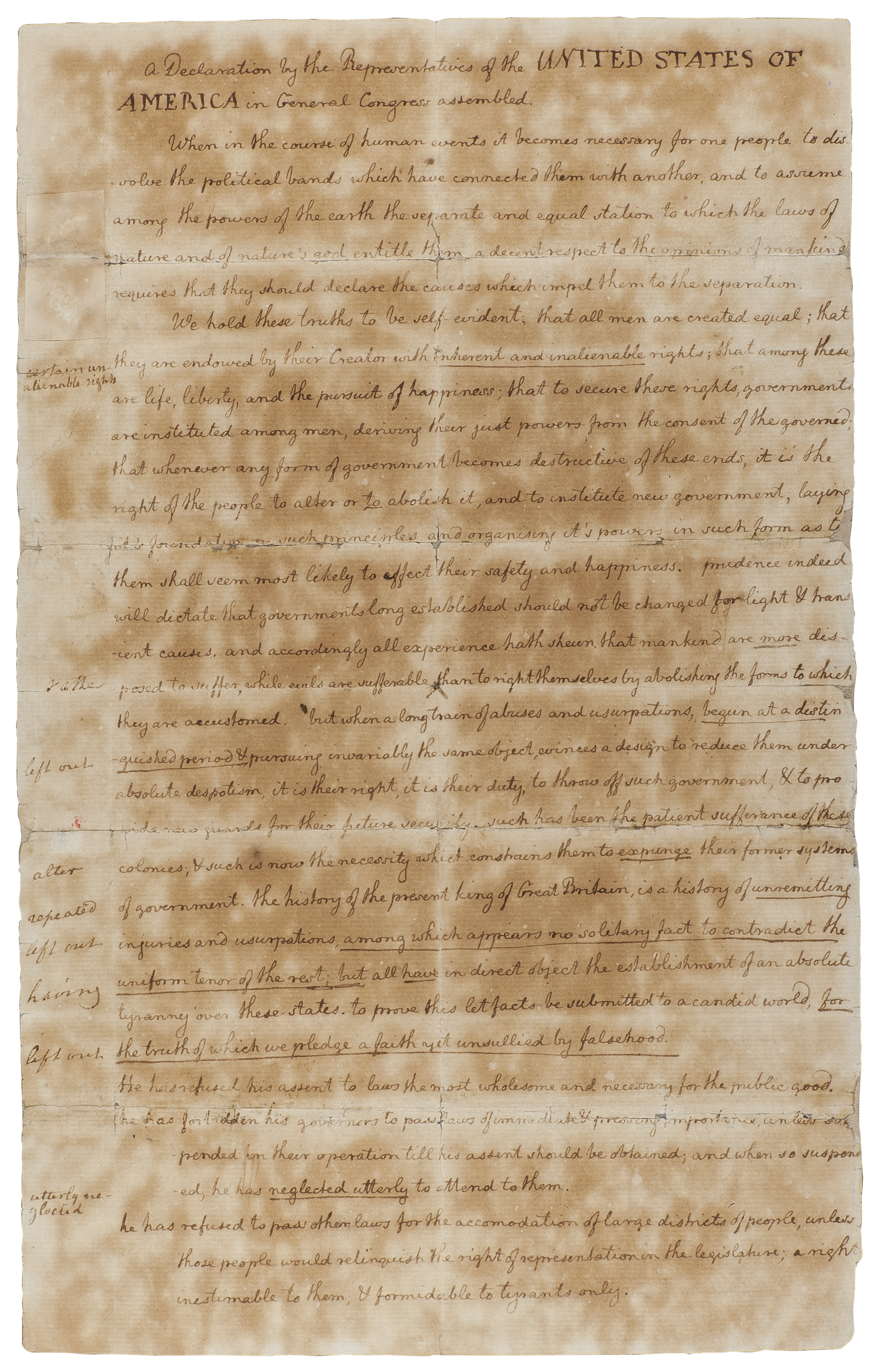

The copy “as originally framed” consisted of two pages handwritten by Thomas Jefferson. This was not a marked-up draft but rather a clean or fair copy of the committee draft. Some years later, it seems as though Richard Henry Lee’s brother, Arthur, made underlines and notes in the margins so that the differences between the committee draft and the final Declaration were more visible on the page.

Richard Henry Lee’s grandson of the same name presented the document to the American Philosophical Society nearly fifty years later. John Vaughan, the librarian of the society, corresponded with Jefferson in an effort to learn more about the manuscript. But Jefferson could not give “any particular account of the paper.” He simply remembered that he had created fair copies of the draft which he had “sent to distant friends who were anxious to know what was passing.”

The copy “as agreed to by the House” is not known to survive. It seems likely that Jefferson sent one of the first printings of the Declaration—either John Dunlap’s broadside or the July 6 issue of the Pennsylvania Evening Post. But the printed version was separated from the handwritten draft sometime after Richard Henry Lee received Jefferson’s letter and its enclosures.

Sometime in mid-July 1776, Richard Henry Lee reviewed the fair copy and the final version of the text, as Thomas Jefferson had expected. On July 21, he responded to Jefferson with thanks for his letter and its enclosures. Lee wrote: “I wish sincerely, as well for the honor of Congress, as for that of the States, that the Manuscript had not been mangled as it is. It is wonderful, and passing pitiful, that the rage of change should be so unhappily applied.” However, Lee could see the bigger picture: “the Thing is in its nature so good, that no Cookery can spoil the Dish for the palates of Freemen.” The people who had hungered for independence would be satisfied with any declaration. The action—the “Thing”—was more important than the contents, at least in the short term.

Where to See It In Person: These Truths Special Exhibition at the American Philosophical Society, April–December 2026