Papermaking and Parchment

The copy of the Declaration of Independence that is associated with a Rittenhouse was printed on parchment, not paper

The Monoshone Creek, northeast of where the Schuylkill River meets the Wissahickon Creek, powered the first paper mill on the land which, eighty-six years later, became the United States of America. William Rittenhouse immigrated to Pennsylvania and established this mill, about a mile southwest of the settlement of Germantown. A flood destroyed the first mill, but Rittenhouse was committed to making this site and this business work. He signed a 990-year lease for the land and water rights. William Rittenhouse died in 1708, but his son kept the papermaking business going. For two decades, the Rittenhouse mill was the only paper mill in British North America until Nicholas’s brother-in-law set up his own operation a few miles away. Still, the Rittenhouse name was synonymous with paper.

It is ironic, then, that the copy of the Declaration of Independence that is associated with a Rittenhouse was printed on parchment, not paper. David Rittenhouse, William’s great-grandson, was born in a house next to the paper mill. His father, Nicholas’s youngest son, decided to leave papermaking behind and move the family west to Norriton, where he became a farmer. When he was a boy, David Rittenhouse built a wooden model of a watermill—said to be the first of many instruments Rittenhouse crafted on his path to becoming a famed and largely self-taught astronomer and clockmaker. When John Adams met Rittenhouse in September 1775, Adams described him as “a Mechannic, a Mathematician, a Philosopher and an Astronomer.”

David Rittenhouse stretched beyond his scientific interests to meet the demands of the American Revolution. In fact, he was at the center of Philadelphia politics and wartime preparations in the summer 1776. He was a member of the Pennsylvania Assembly and the Committee of Safety, and in his spare time, he worked with his younger brother Benjamin to forge iron clock weights to replace the lead that Philadelphians had removed from their clocks to support the war effort.

On July 8, 1776, Rittenhouse was most likely in attendance for the public reading of the Declaration of Independence outside of the Pennsylvania State House. That same day, he was elected to the Pennsylvania constitutional convention alongside Timothy Matlack, who would soon be tasked with inscribing the Declaration on parchment for the Continental Congress to sign, and Benjamin Franklin, who was unanimously chosen as president of the convention. Over the coming weeks, Rittenhouse’s role in the convention expanded dramatically. He became intimately involved in every part of the drafting process, from the preamble to the declaration of rights to the plan of government.

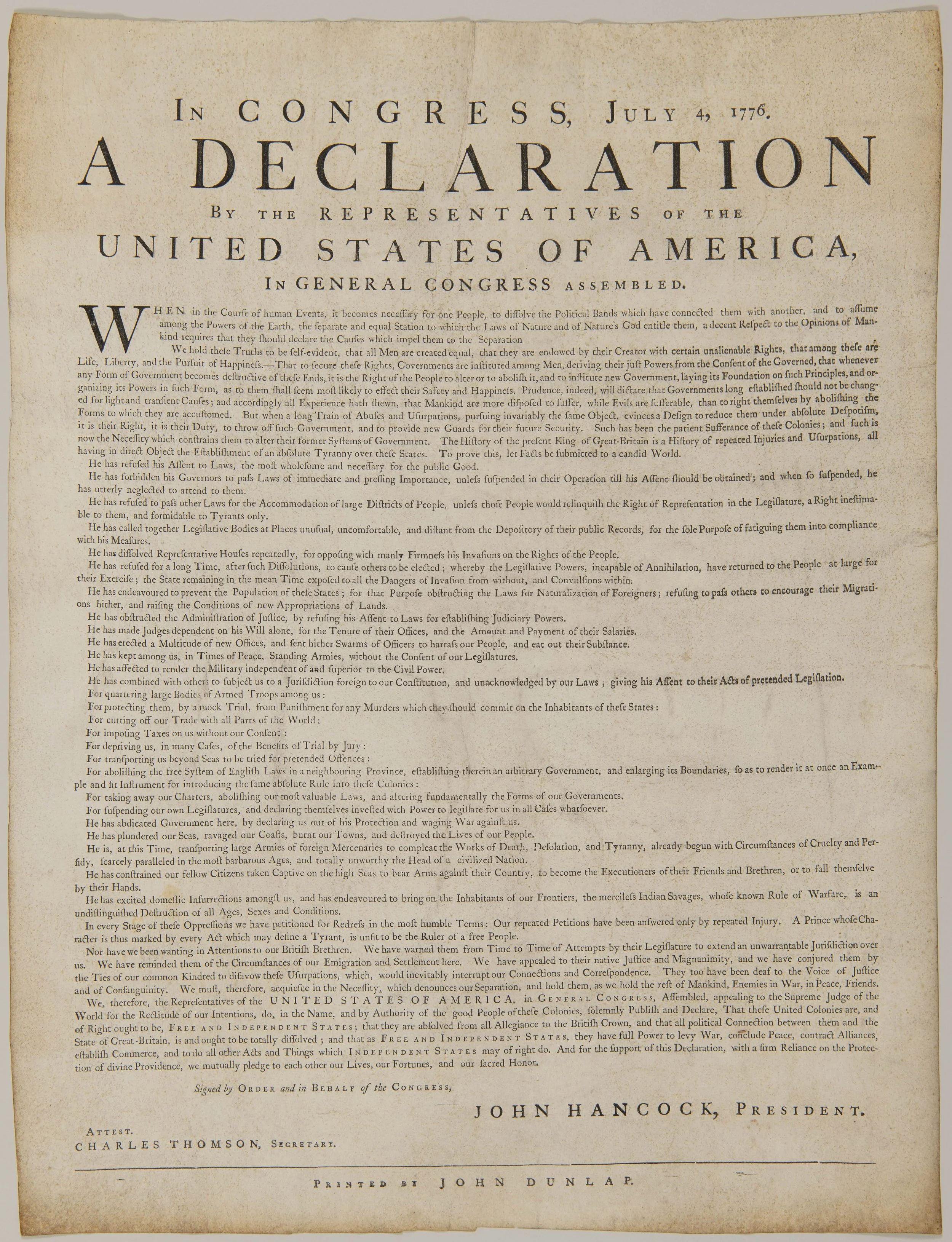

Sometime, whether during these tumultuous weeks in the summer and fall of 1776 or later, David Rittenhouse acquired a unique printing of the Declaration of Independence, created by John Dunlap. After his office had produced hundreds of broadsides on paper for myriad audiences, and after he had published the Declaration in his Pennsylvania Packet, Dunlap decided to print one more copy of the Declaration.

His typesetters had to assemble the text from scratch, and they used a wider form. Instead of pressing the ink onto a sheet of paper, Dunlap imprinted the Declaration on a piece of vellum, or parchment made from calfskin. There is no clear record of why Dunlap made it. Perhaps the Continental Congress had asked Dunlap to print the Declaration on something more durable than paper. Maybe they considered signing a printed rather than handwritten parchment. It is possible that Dunlap produced this broadside of his own volition, for his own reasons.

Regardless of why or precisely when John Dunlap created this broadside, it ended up in the hands of David Rittenhouse. James Mease donated the parchment to the American Philosophical Society in 1828 and, by his account, it came from Rittenhouse’s papers. Mease had served alongside Rittenhouse in the Committee of Safety in 1776. It has been difficult to precisely triangulate the connections between John Dunlap, David Rittenhouse, and James Mease, but ultimately, the donation to the American Philosophical Society made sense. Rittenhouse had succeeded Benjamin Franklin as the society’s president from Franklin’s death in 1790 until Rittenhouse’s own death six years later.

Where to See It In Person:These Truths Special Exhibition at the American Philosophical Society, April–December 2026