The Newport Press

Five months after he printed the Declaration, Solomon Southwick decided to leave Newport, but first, he buried his printing press

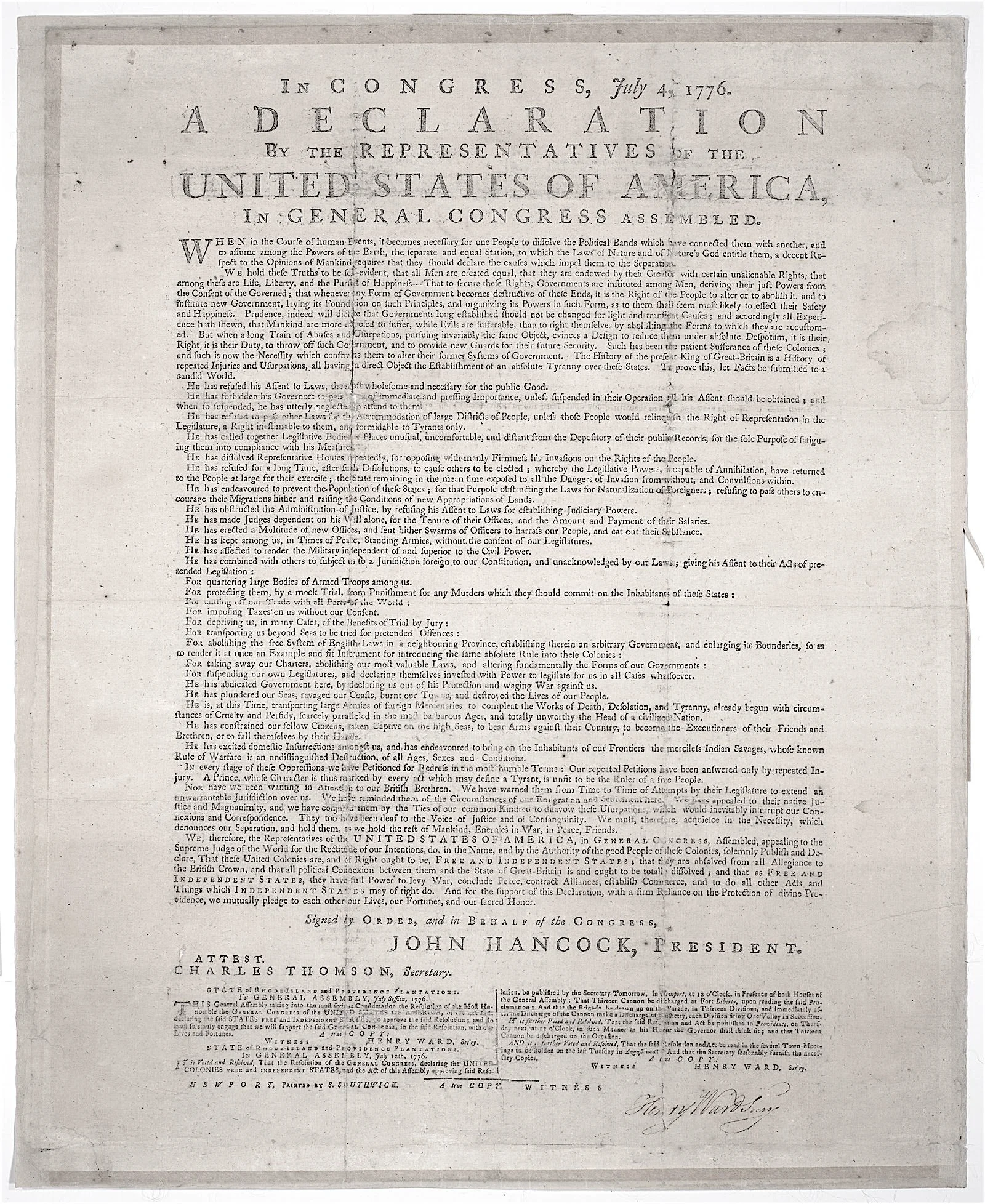

In the summer of 1776, Solomon Southwick printed the Declaration of Independence for the state of Rhode Island. Months later, he buried his printing press in his backyard.

When the Declaration of Independence reached Rhode Island about a week after July 4, 1776, the General Assembly issued their formal support for the Continental Congress’s decision, pledging their “Lives and Fortunes” alongside the delegates in Philadelphia. On July 12, the assembly further resolved, “That the Resolution of the General Congress, declaring the UNITED COLONIES free and independent STATES, and the Act of this Assembly approving said Resolution,” should be proclaimed first in Newport the next day, then in Providence, and finally “in the several Town-Meetings to be holden on the last Tuesday in August.”

Solomon Southwick provided broadsides for the assembly to send to each of the towns. He included the Declaration of Independence and the assembly’s resolutions, making it clear to people across Rhode Island that both their delegates in the Continental Congress and their representatives in the assembly approved the Declaration. At the bottom of the broadside, Southwick indicated that this was “A true COPY” of the texts and the assembly’s secretary, Henry Ward, signed his name attesting to this fact.

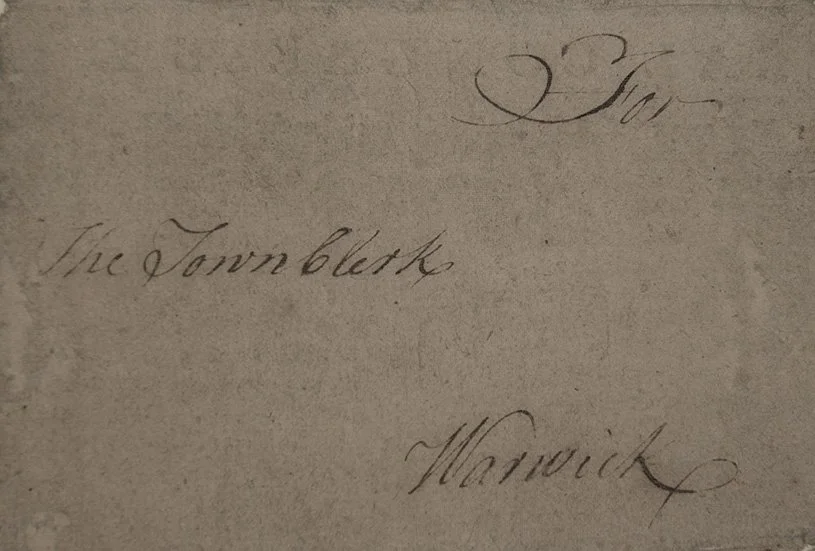

One of the surviving Southwick broadsides remains in the Portsmouth town clerk’s office. Another was sent to the town of Warwick and is now in the library of Washington University in St. Louis. On the back, it is addressed “For The Town Clerk Warwick.” Warwick was near the site of a revolutionary act in June 1772 which is remembered as the Gaspee affair, when a British schooner that had enforced the Navigation Acts off the coast of Rhode Island ran aground and was then boarded and burned. One of the concerns resulting from what happened with the Gaspee was that Americans would be sent to England for criminal trials—a concern which ended up in the list of grievances in the Declaration of Independence.

The printing press Solomon Southwick used to create the broadsides of the Declaration for Warwick, Portsmouth, and other towns in Rhode Island had a storied history. Almost seventy years earlier, Benjamin Franklin’s older brother, James, had imported the press from England. In the 1720s, he set up the press in Newport, and after James Franklin’s death, his wife, Ann, took over. Eventually, both the press and the newspaper that Ann and her son had launched, the Newport Mercury, were Southwick’s.

In December 1776, British forces set their sights on Rhode Island. Five months after he printed the Declaration, Solomon Southwick decided to leave Newport, but first, he buried his printing press. He hoped to keep his press out of enemy hands, and supposedly hid his press in the ground behind his home. Unfortunately, the press was uncovered by the British, reassembled, and during the occupation of Newport, it was used to print a loyalist newspaper. Both the printing press and the revolutionary texts Southwick used it to publish are testament to how quickly tides turned in 1776.

Where to See It Online: Washington University in St. Louis