Last Remains

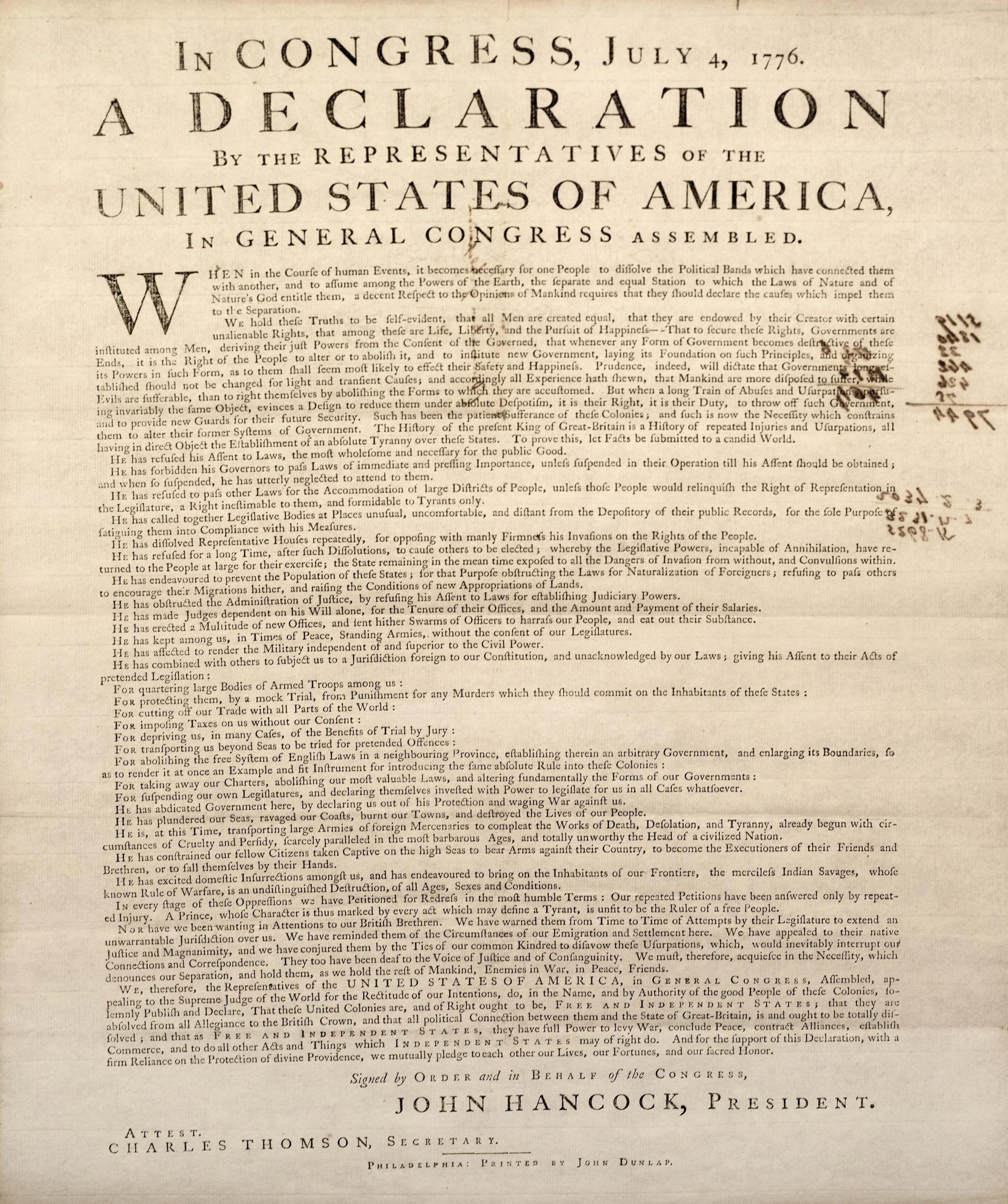

In 1983, Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, acquired one of the broadsides John Dunlap printed in July 1776. The broadside had been stored for years at a plantation outside of Edenton, North Carolina. Evidence suggests a connection between this broadside and a delegate from Edenton, Joseph Hewes.

The lead-up to independence was a challenging time for Joseph Hewes. He was busy with committee work and, for a long time, he was the only North Carolina delegate present in the Continental Congress. “I Am willing to spend the last remains of life in Our Cause in any way I can be most usefully employed,” he wrote in March 1776. But he had a variety of ailments, including a “Violent” headache and an intermittent fever. He thought that the only cure would be to leave Congress, but he refused to leave his home colony unrepresented, and vowed he would “crawl to the Congress Chamber.”

Joseph Hewes wrote frequent letters from Philadelphia to Samuel Johnston, whose Hayes plantation was near Edenton. Hewes was not sure how Johnston felt about independence when, in February 1776, he sent a pamphlet which had become a “Curiosity” in Philadelphia—Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, first published in January. In March 1776, Hewes wrote to Johnston, “I see no prospect of a reconciliation” with Great Britain. He believed that nothing was left “but to fight it out.”

On July 8, 1776, Joseph Hewes wrote a lengthy letter to Samuel Johnston. He mentioned that John Penn, one of North Carolina’s other delegates, had arrived in Philadelphia with “time enough to give his vote for independance” Hewes enclosed the Declaration of Independence for Johnston to read, and further explained that “all the Colonies voted for it except New York, that Colony was prevented from Joining in it by an old Instruction,” but “it is expected they will follow the example of the other Colonies.” By July 8, there were a few different printings of the Declaration of Independence available in Philadelphia. But, given that a Dunlap broadside ended up at Samuel Johnston’s plantation, it seems possible that Hewes may have sent the Dunlap broadside to Johnston.

Hewes was prescient when he wrote in the spring of 1776 that he was willing to spend the “last remains of life” for the cause of independence. He died in Philadelphia in November 1779, shortly after resigning from the Continental Congress because of poor health. However, Hewes’s signature on the parchment copy of the Declaration survives, and he has remained associated with this particular Dunlap broadside.

The Dunlap broadside went from the North Carolina plantation to the auction block in 1983 and sold for $375,000 to Williams College. This pricey purchase, funded by alumni donations, was motivated by the opportunity to have early printings of key founding documents—the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the United States Constitution—in the Chapin Library to educate generations of students.

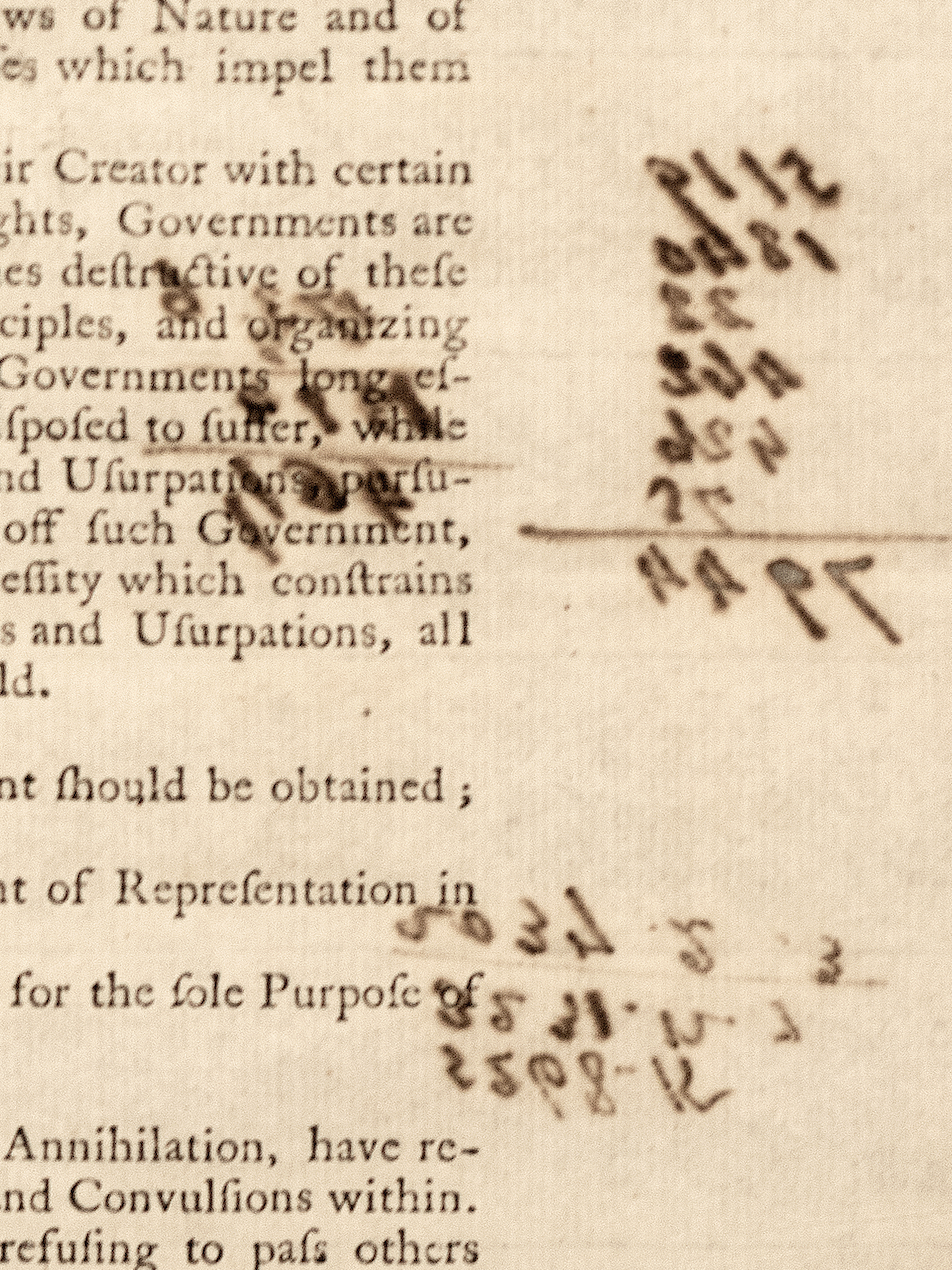

In fact, the copy of the Constitution in their collection was also printed by John Dunlap, and it is a draft, not the final version. The Constitution is marked up with handwriting, and the back of the Declaration has some notations that have bled through to the front of the document. One annotation labeled the document as the Declaration of Independence. There are also some mathematical equations scratched near the edge of the paper.

Where to See It Online: Chapin Library, Williams College