Freshest News

The American Gazette only lasted six weeks, but those weeks coincided with the Declaration of Independence

On Tuesday, June 18, 1776, John Rogers printed the first issue of the American Gazette, or the Constitutional Journal in Salem, Massachusetts. He did not have his own printing press. He was working out of the office of a more established printer, Ezekiel Russell.

Still, Rogers had high hopes for his newspaper. He promised to publish the newspaper every Tuesday with “the freshest and most important Intelligence,” and to make each issue “as entertaining as may be.” He thanked the “good Ladies and Gentlemen, who have so cheerfully, and in such Numbers appeared to encourage” the American Gazette with their subscriptions, at the “moderate” price of eight shillings per year, half paid up front and half paid after six months.

John Rogers’s newspaper did not last a year, or six months, or even two months. It seems that the final issue was printed on July 30, 1776. The American Gazette only lasted six weeks, but those weeks coincided with the Declaration of Independence.

Little is known about John Rogers or why he decided to print a newspaper in Salem. Rogers’s contemporary, Isaiah Thomas, did not have much to say in his History of Printing in America. He noted that Rogers was born in Boston and learned the printing trade as an apprentice to William McAlpine, a Scottish immigrant. According to Thomas, McAlpine was a “royalist” who evacuated Boston with the British forces in the spring of 1776. The records of the Loyalist Claims Commission back up this account. McAlpine left behind his printing presses and type, in addition to his well-furnished ten-room house in Boston—all of which he valued at £800.

John Rogers’s political views were quite different from his one-time mentor. When he launched the American Gazette, Rogers told his subscribers that “the GLORIOUS CAUSE the AMERICAN COLONIES are so Unitedly interested in” made the publication of a newspaper “agreable to every Friend to the Rights and Liberties of Mankind.” People in Massachusetts already had endured years of disruption and uncertainty. Rogers understood that, as the colonies transitioned from British rule to independence, newspaper readers would need access to timely information and essays reflecting on the state of affairs.

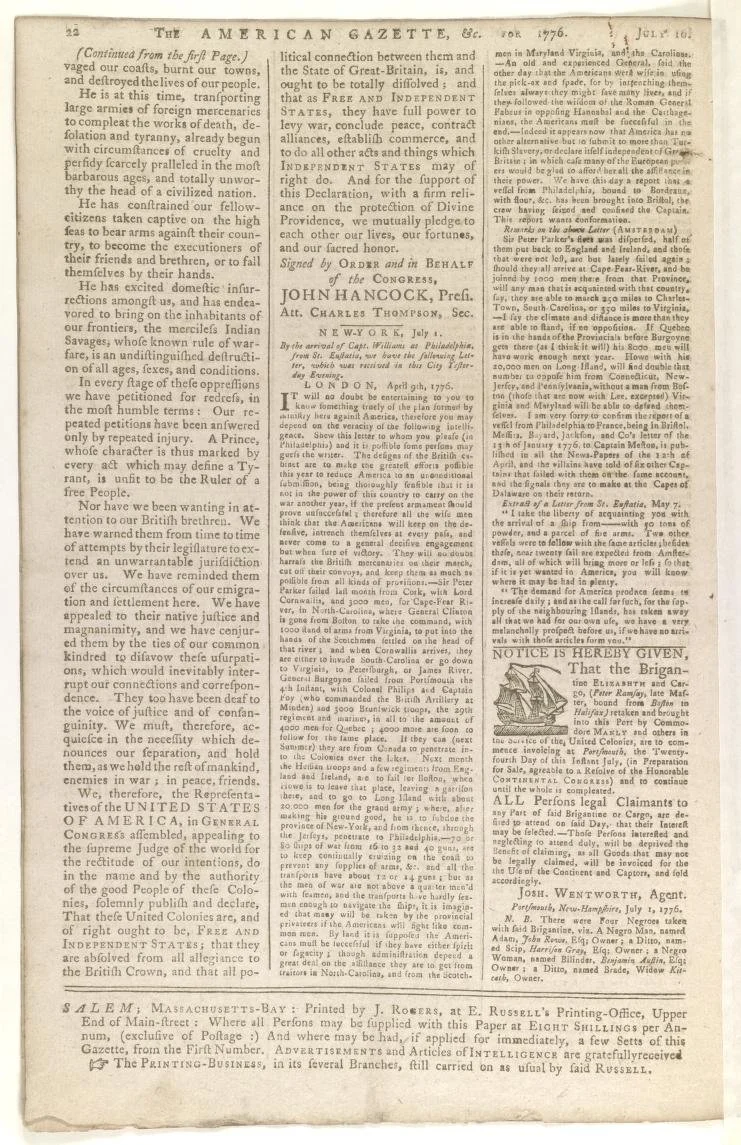

At a time when more established printers were eliminating ornamentation from their newspapers to save on paper and squeeze in more text, Rogers featured a large ornament in the masthead of the American Gazette: an open news journal, sitting above a ship, flanked by an Indigenous man with a bow and arrow and a winged Mercury-like figure with a trumpet. These elements marked Rogers’s newspaper as timely and distinctly American. It was not an original design. In fact, the Pennsylvania Journal, printed in Philadelphia, was using a nearly identical masthead engraving at this time. Both newspapers featured the Declaration of Independence the same week, under the same image.

It took about ten days for the Declaration of Independence to reach Salem, Massachusetts. John Rogers was able to print the text in the fifth issue of his newspaper on Tuesday, July 16, 1776.

The American Gazette was the first Massachusetts newspaper printing of the Declaration. The text filled three columns on the front page with a note to readers to turn to the last page to read the rest. (Spot the typo!)

For a four-page newspaper, typesetters prepared and printed the first and last pages at the same time, on one side of a long sheet of paper. Rogers and the other workers in Ezekiel Russell’s printing office needed to work quickly to print the Declaration of Independence, so it made sense to set the text to print on the same sheet, rather than continuing onto the interior pages.

Two weeks after he published the Declaration of Independence, John Rogers printed the last known issue of the American Gazette. He did not give any suggestion that this issue would be his last—perhaps he did not even know. Although Rogers’s newspaper was short-lived, it lived during a consequential moment.

Where to See It Online: Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.