Philadelphia or Baltimore

John Dunlap could not be in two places at the same time

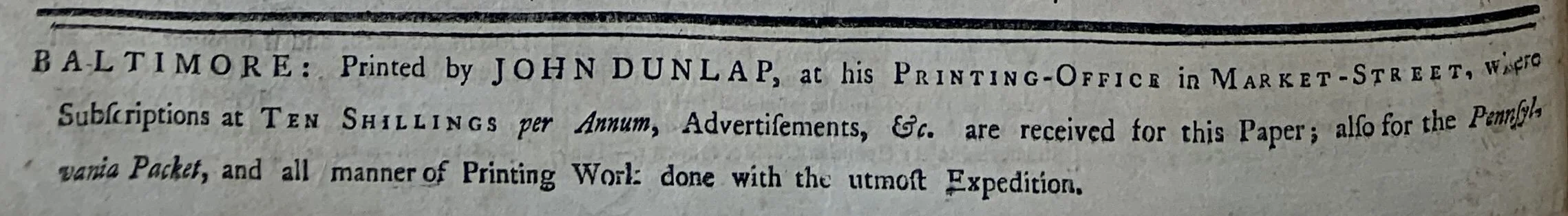

Baltimore, Maryland has had many nicknames. Charm City. The Monumental City. The Greatest City in America. And, since 1988, The City That Reads. Back in 1776, Baltimoreans read the Declaration of Independence in their newspapers, beginning on July 9 with Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette. This newspaper was printed by John Dunlap at his office on Market-Street. Or was it?

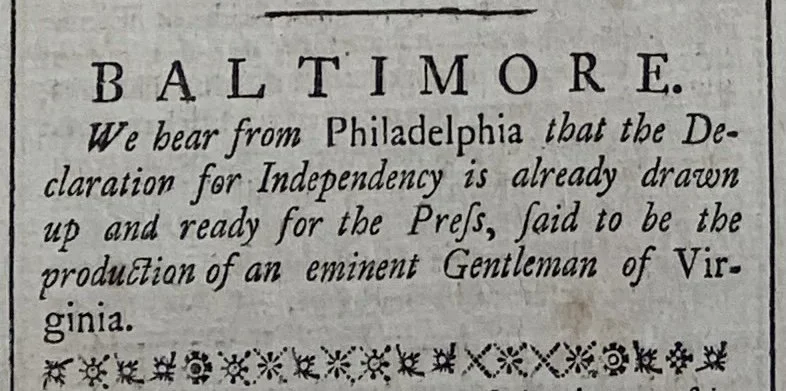

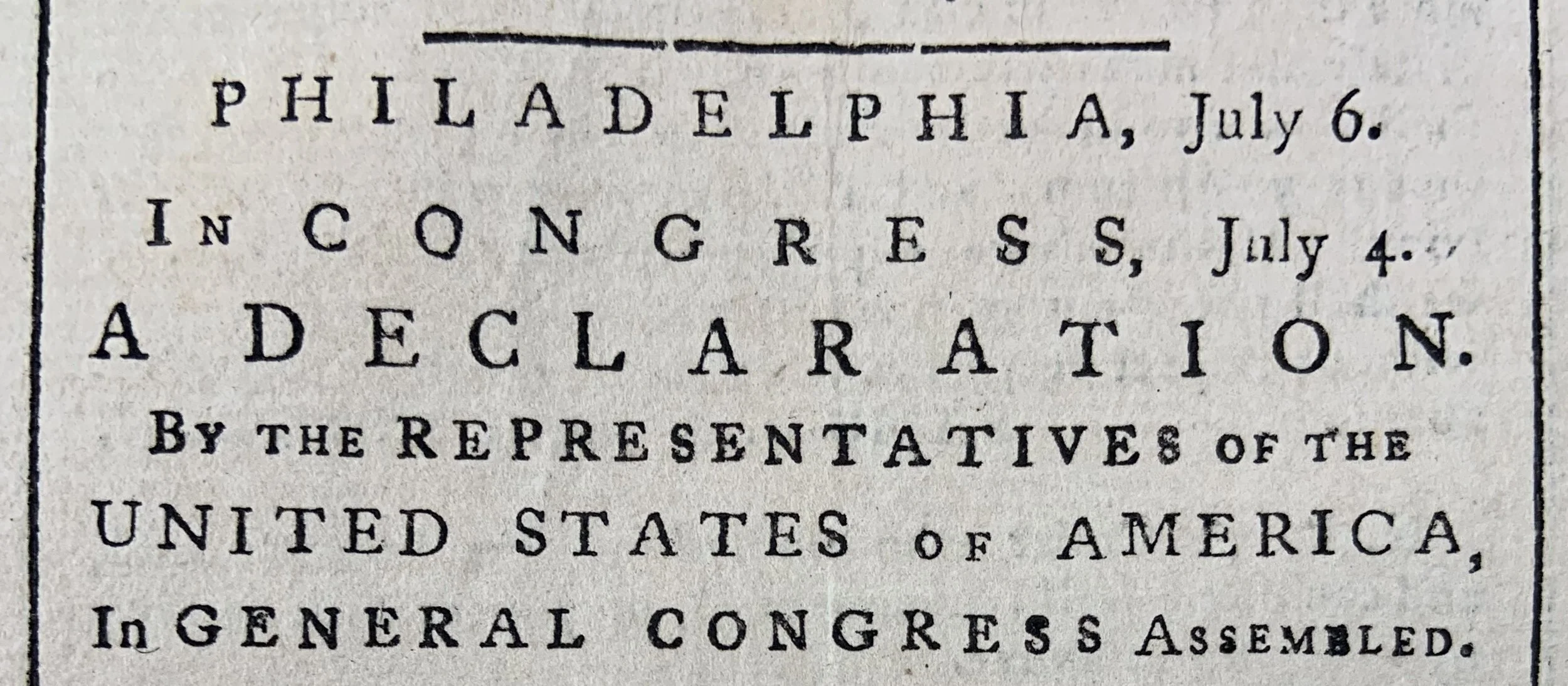

John Dunlap was the first printer of the Declaration of Independence. On Thursday, July 4, the Continental Congress shared the approved version of the text with Dunlap, who printed broadsides or poster-sized sheets in his printing office at the southeast corner of Second and Market Streets in Philadelphia. On Monday, July 8, Dunlap also printed the Declaration in his weekly Philadelphia newspaper, Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet. On Tuesday, July 9, the Declaration was in Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette, printed in his other office on a different Market Street, in Baltimore. Two newspapers, printed within two days, in two cities that were 100 miles apart.

John Dunlap could not be in two places at the same time. Although both of his newspapers were printed under his name, Dunlap relied on teams of people in his Philadelphia and Baltimore printing offices. His key partner in Baltimore was James Hayes, Jr., a young printer who handled the day-to-day responsibilities of the printing office.

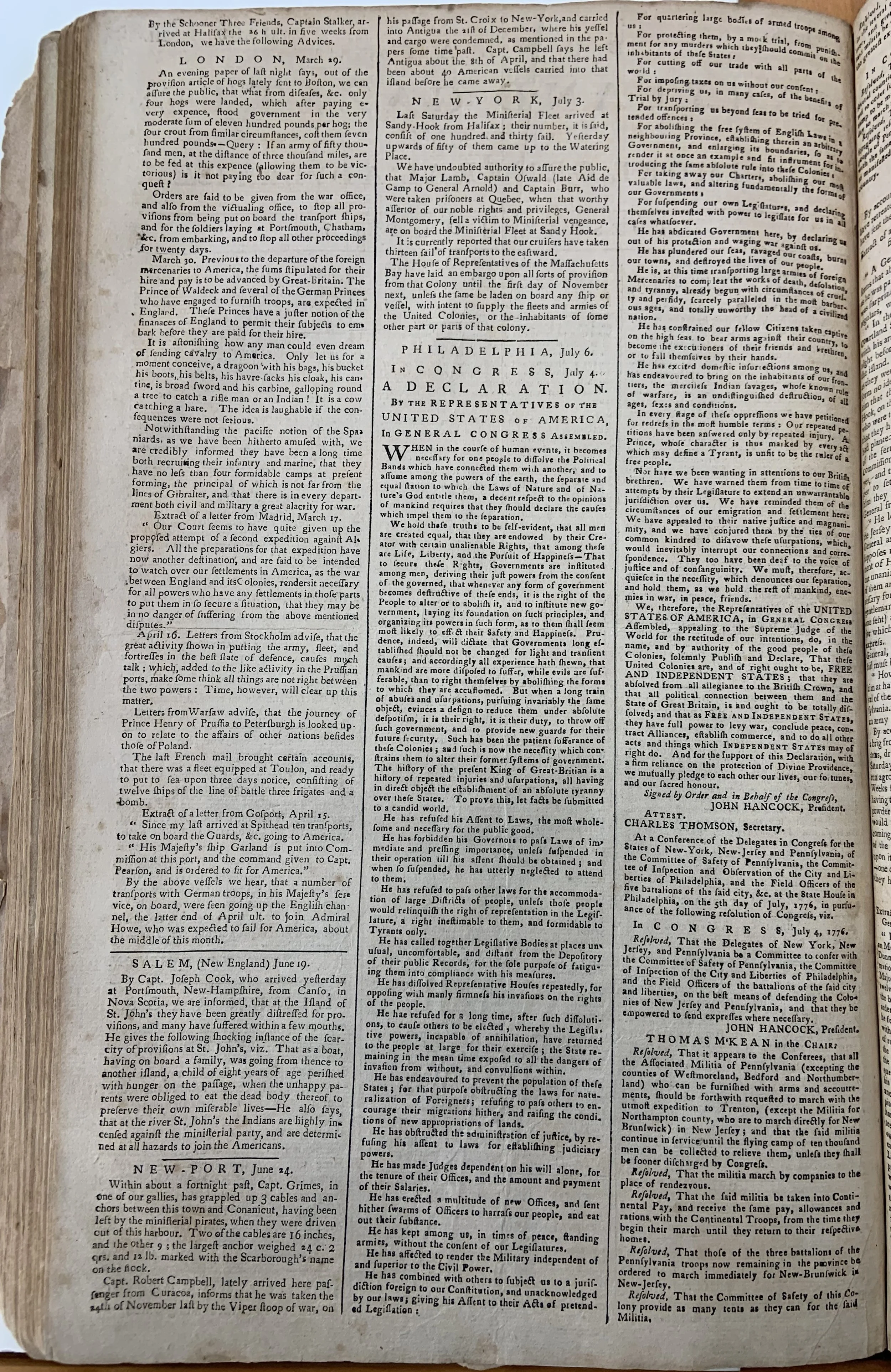

James Hayes, Jr. had prepared readers of Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette for the news of independence. The previous week’s issue, dated July 2, said: “We hear from Philadelphia that the Declaration for Independency is already drawn up and ready for the Press, said to be the production of an eminent Gentleman of Virginia.” We know that this “eminent” Virginian was Thomas Jefferson, the principal author of the Declaration. It was widely reported that, on July 1, the Continental Congress was going to debate whether or not to declare independence. Hayes did not know that, on July 2—the same day as the weekly publication of Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette—Congress made their decision and turned their attention to the Declaration, their explanation to the world.

Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette was the only newspaper in 1776 that attributed the Declaration of Independence to a specific author. Otherwise, the Declaration was thought of as the product of the whole Continental Congress, bearing the printed signatures of President John Hancock and Secretary Charles Thomson as it circulated through the United States’ newspapers. In fact, Thomas Jefferson was not widely known to be the principal author of the Declaration until the 1790s, when he was Secretary of State in George Washington’s administration. James Hayes, Jr. must have gotten this information about the Declaration’s authorship from someone in Philadelphia—whether from John Dunlap or someone in Congress. Whether it was information disclosed in secret or intended to be made public remains unclear. This tidbit never appeared in Dunlap’s Philadelphia newspaper.

James Hayes, Jr. regularly communicated with John Dunlap, but he also relied on the work of other printers. The July 9 issue of Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette makes this clear. The Declaration of Independence appears on the second page of the newspaper under the heading “Philadelphia, July 6.” This suggests that Hayes and the other laborers in Dunlap’s Baltimore office did not copy the Declaration from one of Dunlap’s broadsides. Instead, it seems that they copied the text from the first newspaper printing, the Pennsylvania Evening Post, dated July 6, 1776 and printed by Dunlap’s Philadelphia competitor, Benjamin Towne.

Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette offers an important reminder that each issue of a newspaper reflected the work of a number of people. In the summer of 1776, the Declaration of Independence appeared in only one newspaper that was printed under the name of a woman: Mary Katharine Goddard, another Baltimore printer and the subject of stories to come. One person or printing partnership was named on the page, but many individuals—including paid and unpaid laborers, women and other family members, and enslaved people—contributed to the printing process.

Where to See It in Person:

American Antiquarian Society