Self-Evident Falsehood

In the Scots Magazine, “An Englishman” complained about two phrases that have become the most well-known and treasured parts of the Declaration

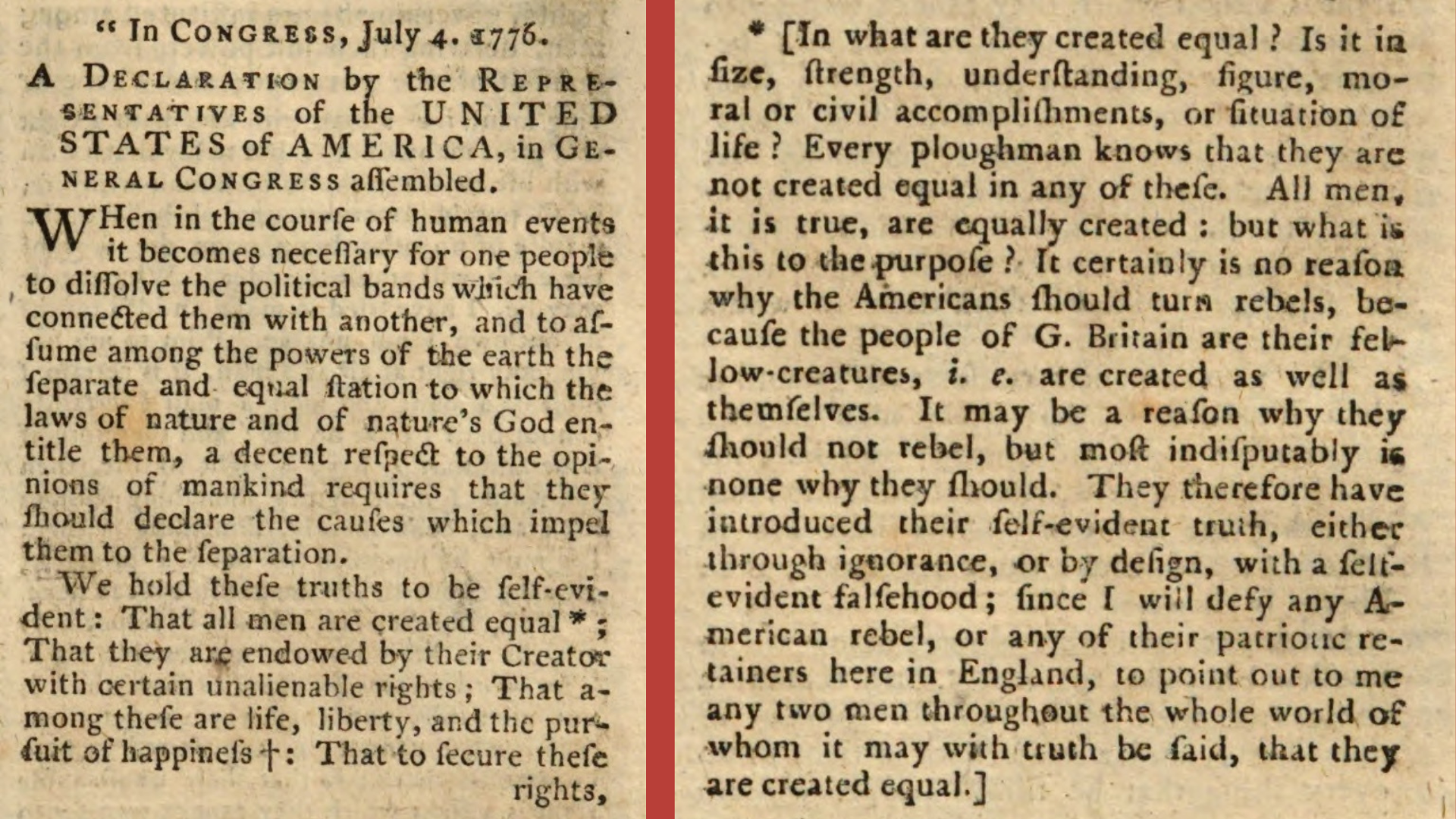

The Scots Magazine was a periodical published in Edinburgh at the end of every month by Alexander Murray and James Cochran. They printed the Declaration of Independence in the August 1776 issue. But, in this Scottish magazine, “An Englishman” controlled the narrative.

In the Scots Magazine, the Declaration was footnoted with “some remarks by a writer under the signature of An Englishman.” This pseudonymous writer asked Murray and Cochran to publish “some thoughts on the late Declaration of the American Congress.” There were so many pamphlets on the “American rebellion” that it seemed fruitless to publish another one. Instead, “An Englishman” shared some notes to provoke questions and influence how readers of the Scots Magazine understood the Declaration.

“An Englishman” was appalled by the Declaration. He understood that the Continental Congress wanted to use this text to justify their decision to separate from Great Britain. But, in a short introduction to the text, “An Englishman” claimed that the Declaration was dishonest and naive. It seems clear that this author could have filled an entire pamphlet with his thoughts, but he contained them to two lengthy footnotes.

An asterisk following the phrase “all men are created equal” directed readers to a bracketed note. The key point that “An Englishman” wanted to make was that this statement of equality did not justify the decision to declare independence. To his mind, “all men are created equal” was a rationale for reconciliation, not rebellion. The Continental Congress “therefore have introduced their self-evident truth, either through ignorance, or by design, with a self-evident falsehood.”

In his next footnote, marked by a dagger, this writer was even more agitated. “An Englishman” used 707 words—more than half the length of the entire Declaration of Independence—to comment on “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The note stretched onto the next page. “The meaning of these words the Congress appear not at all to understand,” “An Englishman” wrote. He broke down each of the rights which the Congress had defined as “unalienable,” or “that which is not alienable, and that which is not alienable is what cannot be transferred so as to become another’s.”

The first unalienable right, to life, confounded “An Englishman.” He wrote that, “because they cannot transfer their own lives from themselves to a cabbage-stalk, therefore they think it absolutely necessary that they should rebel.”

As for the right to liberty, “An Englishman” claimed that this was “nonsense.” The Continental Congress could not claim that all men had the unalienable right to liberty because “slaves there are in America; and where there are slaves, their liberty is alienated.” “An Englishman” was one of several British commentators in 1776 who called out the hypocrisy of using equality statements to declare political independence while maintaining the institution of slavery.

With the last right, the pursuit of happiness, “An Englishman” lost his temper: “The pursuit of happiness an unalienable right! This surely is outdoing every thing that went before. Put it into English: The pursuit of happiness is a right with which the Creator hath endowed me, and which can neither be taken from me, nor can I transfer it to another. Did ever any mortal alive hear of taking a pursuit of happiness from a man? What they possibly can mean by these words, I own, is beyond my comprehension.”

The commentary from “An Englishman” ended with the second sentence of the Declaration of Independence. But the references continued. Alexander Murray and James Cochran included helpful volume and page numbers to connect the month’s news with previous volumes of the Scots Magazine. In the list of grievances against King George III, they referred back to earlier incidents. For example, the grievance about the king keeping standing armies during times of peace directed readers to Volume 37, page 84: a bill proposed by Lord Chatham in the House of Lords in February 1775, in response to a petition from the Continental Congress. The first grievance in that petition, dated 1774, was about the standing army that had been kept in the colonies since the end of the Seven Years’ War.

The references between volumes of the Scots Magazine gave readers context to the Continental Congress’s complaints. But it was the pseudonymous comments on the opening lines of the Declaration that would have caught readers’ attention in 1776 and still catch readers’ attention today. In the Scots Magazine, “An Englishman” complained about two phrases that have become the most well-known and treasured parts of the Declaration: “all men are created equal” and “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Where to See It Online: University of California via HathiTrust