New England Becomes Independent

After the Declaration, Edward Eveleth Powars and Nathaniel Willis got to put their mark on the Chronicle

In his History of Printing in America, Isaiah Thomas wrote about the introduction of printing in Spanish America in the mid-1500s. “The historians, whose works I have consulted, are all silent as to the time when it was first practiced on the American continent,” he complained. Nevertheless, Thomas was able to glean that the first printing press in the Americas was in Mexico City—though a bit earlier than he understood. The earliest book printed in the Americas is dated 1539.

A century later, in 1639, the printing press came to British North America and, more specifically, Isaiah Thomas’s home of Massachusetts. Henry Dunster (ancestor of Hannah Dunster) arrived in Massachusetts in the late summer of 1640 to serve as president of the new college in Cambridge, named Harvard. He quickly married a woman named Elizabeth Glover. Her first husband, Joseph, planned to operate the first printing press in British North America, but died at sea, leaving Elizabeth responsible for the press. Elizabeth died two years into her marriage to Henry Dunster and he took control of the press, despite her eldest son’s claim of inheritance. Dunster employed Samuel Green to run the press, which he later gifted to Harvard.

In 1775, 136 years after the first printing press arrived on campus, Samuel Hall brought another press to Harvard. Hall had printed the Essex Gazette in Salem, Massachusetts since 1768. He left Salem in May 1775 and set up a new printing office in Stoughton Hall at Harvard at “the Desire of many respectable Gentlemen, Members of the Honourable Provincial Congress, and others” who had fled from Boston to Cambridge as the British took control of the city. Samuel Hall, along with his brother and printing partner Ebenezer, recognized the power of newspapers during “this important Crisis—when the Property, the Lives, and (what is infinitely more valuable) the LIBERTY, of the good People of this Country, are in Danger of being torn from them by the cruel Hands of arbitrary Power.”

The Halls’ time in Cambridge printing their newspaper, which they renamed from the Essex Gazette to the New-England Chronicle, proved tragic. At the close of the year 1775, Ebenezer’s wife, Mary, passed away at the age of 21. Ebenezer died, as well, on February 14, 1776. Samuel was unable to print their newspaper the next day, struck by grief as well as a “violent sickness” that came on “just after his brother’s illness commenced.”

A month after Ebenezer’s death, the British evacuated Boston. Rather than returning to Salem, where he had worked alone and alongside his brother for many years, Samuel Hall moved his printing press from the Harvard campus to Boston, to an office on School Street. He published his newspaper next to the tavern named for a sign with Oliver Cromwell’s head—a ghastly visual of revolutions gone wrong. Only six weeks after relocating, Hall handed control of the New-England Chronicle over to Edward Eveleth Powars and Nathaniel Willis, who moved the printing operation to Queen Street. Perhaps the year of loss and disruption had taken too much of a toll on Hall, or perhaps he wanted to refocus his business. Either way, he missed out on the opportunity to print the Declaration of Independence.

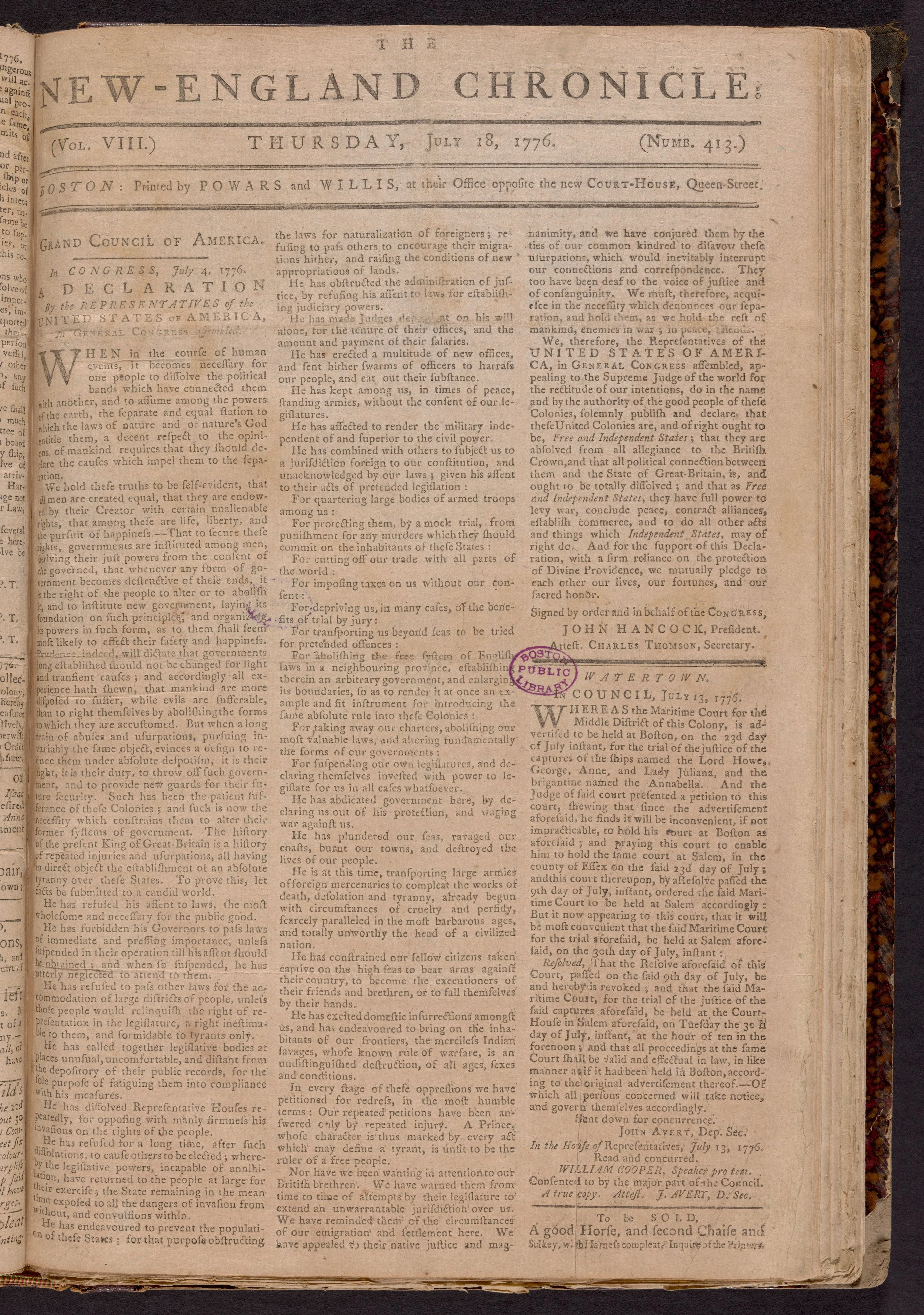

Powars and Willis resolved to publish the latest news, foreign and domestic, as well as articles that might “inspire all orders of men with a true spirit of resolution and heroism in support of our invaluable rights and liberties.” They promised to uphold Samuel and Ebenezer Halls’ legacy of condemning “tories and tyrants” and “rendering due praise and honor to the manly and virtuous supporters of the glorious cause of America.” Six weeks into their new roles as printers of the New-England Chronicle, Powars and Willis printed the Declaration of Independence on the front page.

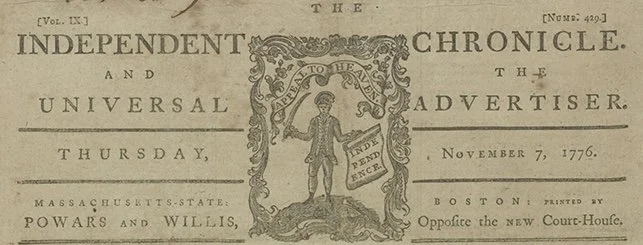

It is clear that the printers wanted to maintain the newspaper’s audience while also making it their own. After the Declaration, Edward Eveleth Powars and Nathaniel Willis got to put their mark on the Chronicle. In September 1776, they changed the name from the New-England Chronicle to the Independent Chronicle. Later in the fall, Powars and Willis added a new ornament to their masthead: a man, standing beneath the motto “APPEAL TO HEAVEN” and holding a sword in one hand and a document reading “INDEPENDENCE” in the other. The design reflected the importance of both printing and fighting for the independent United States.

Where to See It Online: Boston Public Library