Early Intelligence

On July 6, Benjamin Towne had the Declaration of Independence before any of the other newspaper printers were able to share the text with their readers

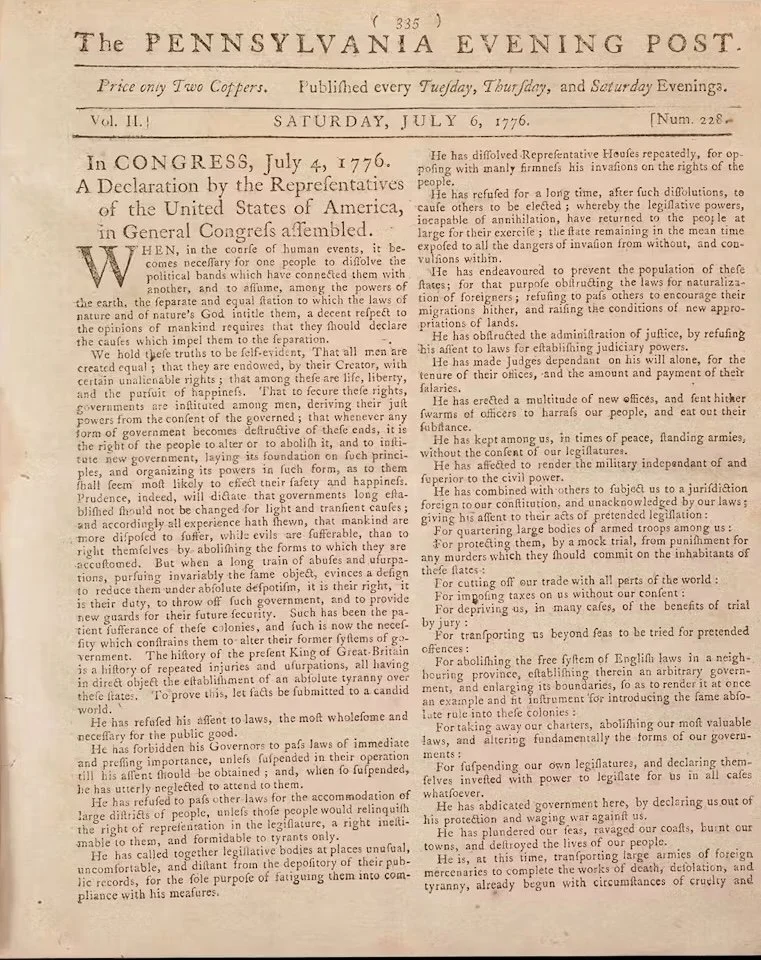

The Declaration’s Journey opens at the Museum of the American Revolution next week, and as one of the guest curators for the exhibit, I want to highlight one of the first objects visitors will see when they walk into the exhibit: the July 6, 1776 issue of the Pennsylvania Evening Post. This was the first newspaper printing of the Declaration of Independence.

Benjamin Towne launched the Pennsylvania Evening Post on Tuesday, January 24, 1775, from his printing office on Front Street in Philadelphia. Towne planned to publish his newspaper on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday evenings, because the mail arrived in Philadelphia on those days. As he explained in his proposal, Towne wanted to “give particular Satisfaction to all Persons anxious for early Intelligence at this important Crisis.”

In the first issue of his newspaper, Towne printed a bit of old news: a petition from the First Continental Congress to King George III, dated October 25, 1774. The petition gives context to the “important Crisis” that Towne acknowledged in his proposal. It included a plea for “peace, liberty, and safety,” and concluded with hope that the king would enjoy “a long and glorious reign over loyal and happy subjects.”

Benjamin Towne’s publishing plan hit a snag by the fourth issue, printed on Tuesday, January 31. He had to alert his readers: “The Eastern Post was not arrived when this Paper went to Press” in the late afternoon. This was a near weekly occurrence during the first few weeks of publication. Still, Towne consistently printed the Evening Post on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays until July 1775, when he needed to make an adjustment. The Continental Congress scheduled a fast day for Thursday, July 20. It was supposed to be an opportunity for reflection on the “present, critical, alarming and calamitous state of these colonies,” in the Congress’s words. All people, regardless of religious belief and practice, were supposed to assemble for public worship and “abstain from servile labour and recreations.” Towne postponed his Thursday newspaper to Friday, and reported that, “Yesterday the FAST, appointed to be held by the Hon. CONTINENTAL CONGRESS, was observed in this city with the greatest solemnity and respect, by persons of all denominations.”

The Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday schedule of the Pennsylvania Evening Post created a unique opportunity for Towne during the first week of July 1776. On Tuesday, July 2, he was able to print the news that, “This day the CONTINENTAL CONGRESS declared the UNITED COLONIES FREE and INDEPENDENT STATES.” On Thursday, July 4, he did not have any further news to report. But on July 6, Benjamin Towne had the Declaration of Independence before any other newspaper printers were able to share the text with their readers.

The issue with the Declaration of Independence was number 228 of the Pennsylvania Evening Post. If the newspaper had been printed once a week, like Towne’s competitors’ papers, he would have published the Declaration in issue number 75 or 76, depending on which day of the week Towne might have chosen. On January 24, 1775, when he pledged to meet the needs of “all Persons anxious for early Intelligence” and printed the Continental Congress’s petition to the king, Towne may not have expected that he would print a declaration of independence from Great Britain eighteen months later. Nevertheless, he clearly hoped to be the first to print such important news.

Where does the Pennsylvania Evening Post fit in The Declaration’s Journey? Alongside the German broadside printed in Philadelphia around the same time, Benjamin Towne’s newspaper printing of the Declaration shows the relatively humble beginnings of the text that has inspired countless political and social movements around the world. In the same pages as the founding document of the United States, Towne included a notice to his subscribers that, if they did not settle their accounts with him immediately, he would “soon be under the disagreeable necessity of DROPPING the Pennsylvania Evening Post, the price of paper and other articles being so greatly advanced.” Printers in 1776, including Towne, recognized the importance of the Declaration and prioritized it despite paper shortages and other precarities of revolutionary times. Other documents in The Declaration’s Journey from other moments in time, from Chile in 1812 to Ireland in 1916, hold similar stories. Be sure to visit the Museum of the American Revolution between October 18, 2025 and January 3, 2027 to see the Pennsylvania Evening Post and many other interesting objects!

Where to See It In Person: The Declaration’s Journey, Special Exhibition at the Museum of the American Revolution, October 2025–January 2027