Dunmore’s Cruel Declaration

When readers opened their newspapers and read the Declaration, their eyes may have drifted to the graphic descriptions of freedom seekers left for dead

On July 20, 1776, John Dixon and William Hunter, Jr. printed the Declaration of Independence in their Virginia Gazette, one day after Alexander Purdie printed an extract of the Declaration in his same-named newspaper. In Dixon and Hunter’s Gazette, the Declaration was on the second page, opposite an extract from the journal of an officer “who was at the late cannonade at Gwyn’s Island.” When readers opened their newspapers and read the Declaration, their eyes may have drifted to the graphic descriptions of freedom seekers left for dead.

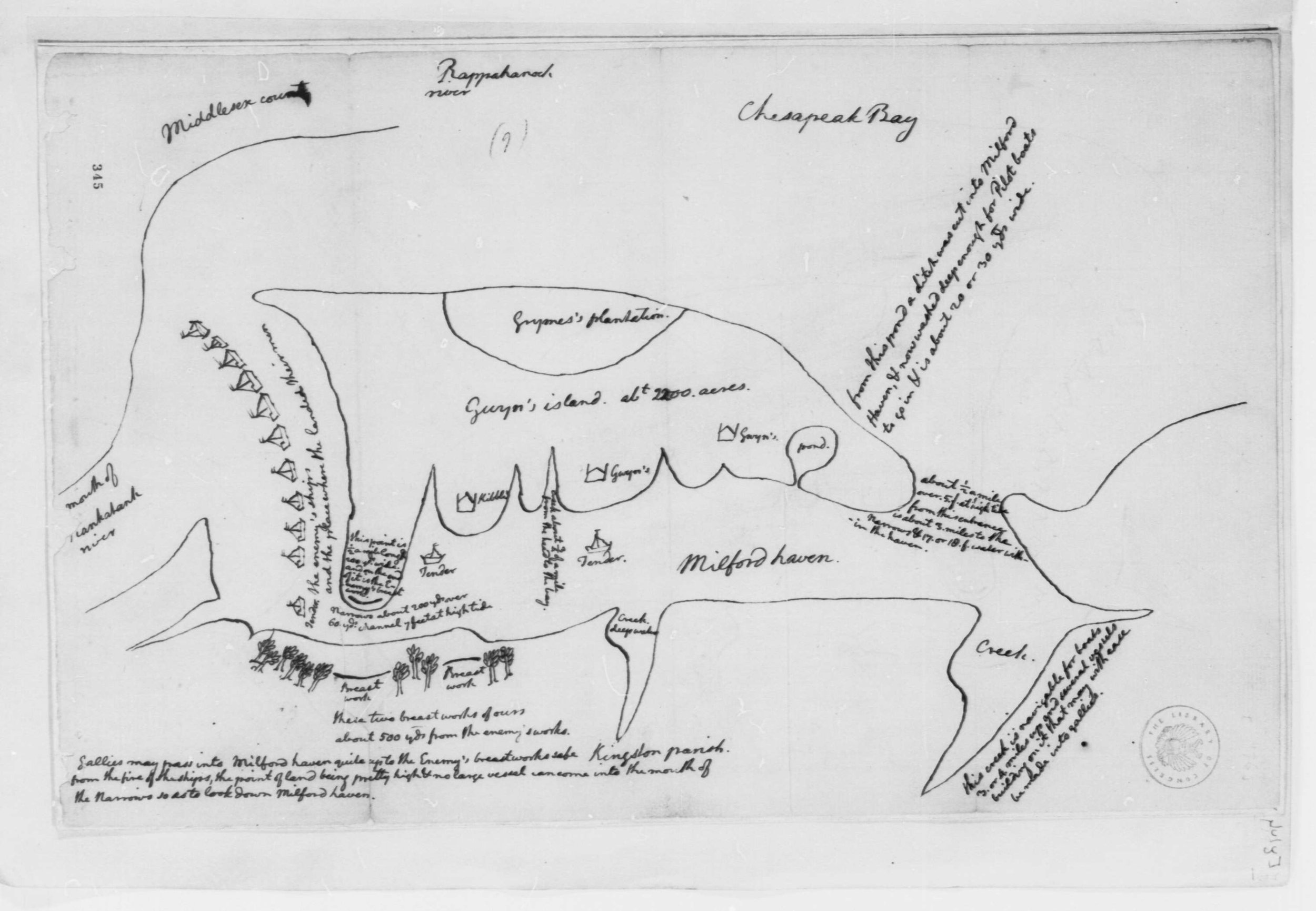

The account from Gwynn’s Island was inextricably linked to the Declaration of Independence—on paper, in the July 20 issue of the Virginia Gazette, but also in the minds of the men who wrote and edited the Declaration. Thomas Jefferson sketched this map of the island in the same weeks when the Continental Congress was discussing independence. Gwynn’s Island was located in the Chesapeake Bay near the mouth of the Rappahannock River and, in June 1776, it was the site of a military engagement. On one side was Brigadier General Andrew Lewis and his Virginia soldiers. On the other side was John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore and Royal Governor of Virginia.

What happened on Gwynn’s Island connects back to Lord Dunmore’s proclamation, issued on November 7, 1775. John Dixon and William Hunter, Jr. printed this proclamation in the Virginia Gazette on November 25, 1775. One line in particular troubled many white Virginians:

“I do hereby further declare all indented servants, Negroes, or others (appertaining to rebels), free, that are able and willing to bear arms, they joining his Majesty’s troops, as soon as may be, for the more speedily reducing this colony to a proper sense of their duty to his Majesty’s crown and dignity. I do further order, and require, all his Majesty’s liege subjects to retain their quitrents, or any other taxes due, or that may become due, in their own custody, till such time as peace may be again restored to this at present most unhappy country, or demanded of them for their former salutary purposes, by officers properly authorised to receive the same.”

In short, Dunmore offered freedom to people in bondage who left their enslavers and joined the British forces. Even before the proclamation itself appeared in the Virginia Gazette, there was evidence of its impact in the newspaper’s advertisements. Robert Brent offered £5 for the return of his enslaved laborer Charles, “a very shrewd sensible Fellow” who was literate and “well known through most of Virginia and Maryland.” Charles was literate and there was “Reason to believe” that he had a “long premeditated” plan “to get to Lord Dunmore.” In the advertisement, his enslaver claimed that “His Elopement was from no Cause of Complaint, or Dread of a Whipping (for he has always been remarkably indulged, indeed too much so) but from a determined Resolution to get Liberty, as he conceived, by flying to Lord Dunmore.”

The Virginia Gazette included a scathing commentary on Dunmore’s proclamation. First off, Dunmore’s offer was contingent on the ability to bear arms, which suggested that “the aged, the infirm, the women and children, are still to remain the property of their masters, masters who will be provoked to severity, should part of their slaves desert them.” Because of this, in the Virginia Gazette, Dunmore’s proclamation was labeled as “a cruel declaration.” But the account from Gwynn’s Island published in the Gazette in July 1776 shows that women and children did, in fact, join Dunmore.

The cannonade at Gwynn’s Island beginning on June 8, 1776, caused Dunmore’s fleet of more than sixty vessels to leave the island—and in quite a hurry. The British ships abandoned anchors, cables, and cannon, as well as people. When the officer whose account was published in the Virginia Gazette paddled over to the island, he witnessed the “deplorable situation of the miserable wretches left behind.” Multiple ships were left burnt on the shoreline. The shallow graves of hundreds of formerly enslaved people who had died from smallpox and fever dotted the island. More people were left near death, including a child “found sucking at the breast of its dead mother,” a “poor wretch half dead making signs for water,” and others trying “to crawl away from the intolerable stench of dead bodies lying by their sides.” It was a “shocking scene,” and this officer blamed Dunmore for his “neglect of those poor creatures.” He hoped that his description was “enough to discourage others from joining him.”

250 years later, Dunmore’s “cruel declaration” and the Declaration of Independence are still in conversation. One document offered freedom to enslaved Americans, and the other was used by generations of Americans to advocate for abolition and equal rights.

Where to See It Online: Library of Congress